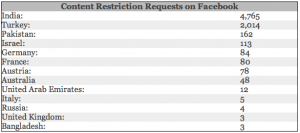

“Facebook’s mission is to give people the power to share, and to make the world more open and connected,” wrote Colin Stretch, Facebook’s general counsel. “Sometimes, the laws of a country interfere with that mission, by limiting what can be shared there.” Though India had by far the most content restriction requests, religious defamation was not the only censorship law with which Facebook complied. Turkey requested 2,014 posts be restricted for defaming the Turkish state or its founder Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. And laws against Holocaust denial led Germany (84), France (80) and Austria (78) to ask for censorship as well. The full list can be seen below. Facebook has declined to comment on how often it complies with these requests, only adding that it doesn’t automatically accede every time. “When we receive a government request seeking to enforce those laws, we review it with care, and, even where we conclude that it is legally sufficient, we only restrict access to content in the requesting country,” wrote Stretch. “We do not remove content from our service entirely unless we determine that it violates our community standards.” Not a national security concern: If these numbers weren’t disturbing enough, they don’t even include all the law enforcement and national security requests that Facebook receives. Between July and December 2013, the U.S. government alone filed 12,598 requests relating to criminal cases; according to Facebook, the company supplied information for 81.02% of the requests. Facebook has also posted a map illustrating all the censorship and surveillance requests the company received between last July and December. “We respond to valid requests relating to criminal cases. Each and every request we receive is checked for legal sufficiency and we reject or require greater specificity on requests that are overly broad or vague,” reads the site description. But while criminal cases pose a public interest, it’s harder to make the same argument for restrictions on free speech. Though Facebook itself has community guidelines on hate speech, it has not always applied them in a transparent or consistent manner. And because it defers to the specific laws of different countries, the policy doesn’t really distinguish between censoring hate speech and aiding political repression.

Facebook’s not alone: The same concern can be applied to Twitter, which has also released data on government requests for censorship. Out of the 377 requests it received from courts and government agencies for content restriction, Twitter says it only complied with 11% of the cases. Though that number may be low, some of the requests had arbitrary reasons, such as India asking Twitter to “remove defamatory content about a manufacturer in India.” It’s hard to justify that request as a matter of public interest. For both Facebook and Twitter, it’s a tough balancing act between guaranteeing a platform for its users and earning the goodwill of state governments. Both sites have faced censorship in the past, and it may seem like good operating policy to abide local laws and cooperate with government requests. But in an online community, it makes little sense to subject users to different sets of rules based on where they are from. These companies have taken the right step towards transparency by releasing this data, but they have much more to go when it comes to devising guidelines that protect their users from unfair censorship.